On January 14, 2022, Hermès International and Hermès of Paris, Inc. filed a trademark and unfair competition lawsuit against Mason Rotschild in the Southern District Court of New York (SDNY). One year later (already!), on February 8, 2023, a 9-member People’s Jury appointed by the SDNY dismissed the case. In essence, the facts were as follows:

Since 1984, Hermès has marketed the Birkin bag, which has become an icon in the world of handbags. A symbol of luxury and exclusivity, each Birkin bag is handcrafted and takes 18 hours to make. Available in different versions, the Birkin bag is sold individually for an entry price of approximately CHF 10,000. At an auction organized by Sotheby’s in 2021, one example sold for USD 226,000. It is not uncommon for women to have to wait more than a year to obtain the precious sesame:

At the time the action was filed on January 14, 2022 in the Southern District Court of New York (SDNY), Hermès was the owner in the United States of the word mark Birkin, as well as of a trade dress mark (which in Switzerland would be described as three-dimensional), represented as follows:

It should be noted that these two trademarks were however only registered in class 18 in the field of leather goods, and not in the field of software and other digital products in class 9.

The defendant, Mason Rotschild, had decided to launch during 2021 at <metabirkins.com> what he described as an “art project”, i.e. the sale of 100 digital reproductions “inspired” by the Birkin bag in faux fur, marketed in the form of NFTs under the name Metabirkins for a unit price of USD 450, with the associated smart contract also providing for a 7.5% royalty on the subsequent sale price of the NFT in the event of subsequent resale:

Hermès raised four claims in support of its action: first, that this marketing violated both its word mark and trade dress rights; second, that it resulted in a dilution of its mark; third, that the registration of the <metabirkins.com> domain name constituted an act of cybersquatting; and finally, that it resulted in an act of unfair competition.

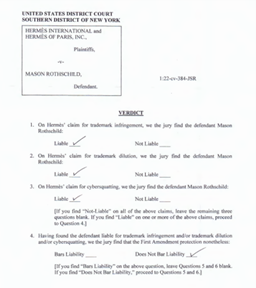

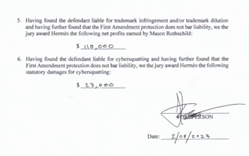

After various procedural twists and turns, Hermes won the case in a decision rendered on February 8, 2023:

Only the action brought under trademark law will be considered here:

In essence, Rotschild was arguing that his design was artistic and that, under the First Amendment (freedom of expression), his design did not violate trademark law.

US Case Law, at least that of the Second Circuit before which this case was brought, considers that the legal assessment of the use of a third party’s trademark in the context of a project presented as artistic or eligible for First Amendment protection must be made in light of two precedents: when the project is primarily commercial in nature, the test to be applied is that of Gruner + Jahr (Gruner + Jahr USA Publishing v. Meredith Corporation, 991 F.2d 1073 [1993]); when, on the other hand, the project incorporates a genuine artistic concept notwithstanding its profit-making nature, the Rogers test (Rogers v. Grimaldi, 875 F.2d 994 [1989]) must be applied.

While the Gruner + Jahr test actually enshrines the classic confusion test as defined in 1961 in the Polaroid case (Polaroid Corporation v. Polaroid Electronics Corporation, 287 F.2d 492 [1961]) (more or less in line with the one resulting from the application or Art. 3 of the Swiss Trademark Act), it follows from the Rogers test that the question of whether there is a violation of trademark law depends on three criteria: first, whether the work in question is one of artistic expression, and thus prima facie entitled to protection under the First Amendment; second, whether the use of the third party trademark bears any artistic relevance to the underlying work; finally, the work in question will not be able to avail itself of the protection conferred by the First Amendment if it is explicitly misleading as to its source or content.

While Hermès argued that the case should be decided under the Gruner + Jahr test, Rotschild argued that it should be decided under the Rogers test. On the basis of the exhibits submitted, and notwithstanding Hermès’ denials on this point, the SDNY found that it could not be ruled out that the project was originally considered to be of artistic merit.

Applying the Rogers test, the SDNY has taken the above criteria and concluded the following:

Judge Rokoff ruled that no summary judgment could be given in favor of either party, and that it was up to the jury asked by Hermes to decide. After a week of trial, the nine members of the jury found that Rotschild could not claim First Amendment protection and that the application of the Rogers test, in particular its third criterion, led to a violation of trademark law.

The judgment is interesting for several reasons:

The efficiency shown by the SDNY in a case with many new issues can only be envied by Swiss litigants. It demonstrates an understanding by US Courts of the business needs of the trademark holders that we can only envy.

Interestingly, Hermès also filed such a registration before the USPTO in class 9 while the case was pending, but the absence of such a registration during the proceedings did not prevent Hermès from winning, even though it only had registered marks in class 18.

Admittedly, the SDNY did not engage in a thorough analysis of the question of whether a class 18 registration could be considered to cover a use in the form of an NFT, which question is admittedly posed in somewhat different terms than those to which the Swiss jurist is accustomed from the standpoint of art. 3 of the Swiss Trademark Act.

However, implicitly, the SDNY answers this question in the affirmative. The woman who buys a Birkin bag does not do so for what she can put in it. She buys it for the image of prestige and belonging to an exclusive community that the exterior of the bag confers.

In other words, what matters is not so much the fact that the properties of a bag (defined, according to the Robert, as a “flexible object made to serve as a container, where one can store, carry various things”) cannot be fulfilled by a digital image of the said bag and that, as such, it cannot be considered as similar to a “bag” in the sense of the aforementioned definition.

What really matters is that the target audience perceives the Metabirkin bag as a Birkin bag; it is not the bag’s properties that matter, but its appearance and what it says about the owner. It is from this perception that a similarity between the products arises, the Metabirkin bag being perceived as the digital transposition of the Birkin bag.

Therefore, in my opinion, and as the SDNY at least implicitly holds, in my opinion correctly, it is sufficient that the target public (whose point of view is decisive) perceives in the digital product an equivalent of the tangible product for the similarity required by the law to admit an infringement of the mark to be achieved. A registration in class 9 would then be useless. However, it must be admitted that the practice has unfortunately not gone down this path. This can only be regretted.

Creators and trademark owners are not done yet. While everyone will undoubtedly agree that the freedom of art stops where the exclusive right is violated, the delicate question consists in knowing at what point this right can be considered as being violated, without emptying of its substance the freedom of expression that must be granted to artists. While Hermès has thus won the first battle, it has not yet won the final victory. To be continued.

Do you have questions about his topic?

Our lawyers benefit from their perfect understanding of Swiss and international business law. They are highly responsive and work hard to find the best legal and practical solution to their clients’ cases. They have acquired years in international experience in business law. They speak several foreign languages and have access to correspondents all over the world.

Avenue de Rumine 13

PO Box

CH – 1001 Lausanne

+41 21 711 71 00

info@wg-avocats.ch

©2024 Wilhelm Attorneys-at-Law Corp. Privacy Policy – Made by Mediago