Since 2023, AI has been monopolizing discussions and monopolizing the spoken word, sweeping everything in its path like a tidal wave.

While the questions are multiplying, the answers are few and far between. The development and use of these tools has become a priority for companies, who rightly see it as a turning point that cannot be ignored. However, a governance framework is needed to provide answers to these many questions.

A. European regulations on artificial intelligence

In the coming weeks, I propose to take a tour of what has gone from being a “Proposal” to becoming the European AI Regulation, now known since it “leaked” on January 22, 2024.

Following the same structure, and at the rate of one publication per week, we will cover in turn: (1) general provisions; (2) general-purpose AI systems; (3) prohibited practices; (4) high-risk practices; (5) transparency obligations; (6) measures to encourage innovation; (7) governance; (8) the register; (9) monitoring and surveillance obligations; (10) codes of conduct; (11) sanctions; and finally (12) issues relating to the delegation of powers.

While we wait for the review of these regulations to begin next week, let’s take a look this week at the current state of copyright issues raised by these systems, in the light of current legal cases.

B. NY Times v. OpenAI and Microsoft

The latest, the action brought on December 27, 2023 before the United States District Court Southern District of New York by the NY Times not only against OpenAI, but also against Microsoft, is undoubtedly the most emblematic since, for the first time, a major player is taking the case to court.

As with many other current actions, the NY Times is claiming massive infringement of its rights; with a 69-page application, the NY Times demonstrates through numerous examples that the results generated by ChatGPT lead in many cases, on the basis of the simplest prompts, to an almost complete reproduction of certain published articles.

In this case, therefore, it’s not just the input data that’s at stake – cases in which the issue of fair use is undeniably acute in the USA – but the result itself (output).

When it comes to output, however, the fair use exception appears far less convincing, at least in this case. The NY Times demonstrates with numerous examples that, in many cases, these results largely reproduce its articles.

For the NY Times, the risk is high that Internet users will give up their subscriptions to the daily newspaper – subscriptions which, as the NY Times points out, are invaluable in maintaining journalistic quality at a time when misinformation has become legion. While the NY Times is primarily concerned, the future of the press as a whole is at stake in this case.

On the face of it, it is hard to see how the conditions for the exercise of fair use could be met, and how, in the light of the claim, and at this stage at least, the defendants could escape recognition of their infringement of NY Times copyright.

On January 8, 2024, OpenAI issued a lengthy letter rejecting OpenAI’s spurious allegations. Unsurprisingly, it points out that, notwithstanding authors’ right to opt out, the entrainment of protected data is a case of fair use. She adds that the examples cited in the application are in fact only rare cases reflecting prompts with a deliberate intention to manipulate the system. To be continued.

C. Business in progress

Since last year, there has been a flurry of cases dealing with copyright issues, both in terms of input data and, to a lesser extent, output.

(I) Infringement of copyright on training data (input)?

In the United States, cases involving training data have included, but are not limited to, the following:

Outside the United States, we can also mention :

(II) Copyright on output?

D. Conclusion

What can we conclude from this overview of the situation at the start of 2024?

(I) Training data

It’s astonishing that OpenAI should take offence at the criticisms levelled at it, when it is clearly seeking partnerships with major players capable of providing it with a massive flow of data.

Thus, in July 2023, it signed a licensing agreement with both Associated Press and Shutterstock, enabling it to exploit their content. On December 13, 2023, it did the same with publishing giant Axel Springer (and we wonder whether it’s shooting itself in the foot, even if the terms of the transaction are obviously unknown to us).

In any case, it’s hard to see why OpenAI would sign such agreements if it didn’t recognize the illicit nature of the reproductions it makes of these data to drive its model.

In any case, the cases currently underway already testify to the procedural difficulties that plaintiffs in such actions are likely to encounter in winning their cases.

The debate is not limited solely to the question of whether these training data infringe the rights of the owners, and whether the developers of these generative tools can claim an exception. First and foremost, the court seized must have jurisdiction to do so. While most of the cases have been brought in the United States, where the developers are based and the question of jurisdiction does not arise, the issue is different when the owners wish to act abroad. The Getty Images case pending before the High Court of Justice of London underlines the fact that the jurisdiction of this Court is an open question, on which the High Court will have to rule. Little examined to date, aspects of private international law should not be underestimated.

Secondly, assuming that the Court has jurisdiction, the plaintiffs must have active legitimacy, i.e. they must demonstrate that works in which they hold rights have actually been reproduced for use as training data; a mere allegation that such exploitation appears more than likely in view of the number of images reproduced does not seem sufficient. The bar could therefore prove particularly high.

We can be sure that solutions will be found in the years to come, for example in the form of remuneration rights or extended collective licenses, without necessarily going so far as to offer a blank check for such practices, as Japan, Singapore or even possibly Israel have chosen to do.

(II) Results generated

Although Ukraine opted in 2023 for the introduction of a sui generis right protecting the results generated by generative tools, this choice seems to remain an exception. More generally, the decisive question is whether the user has made a sufficient contribution to the sequence of prompts and their arrangement to be considered an “author”.

While this criterion seems to be the rule, we have to admit that its interpretation varies widely from one country to another:

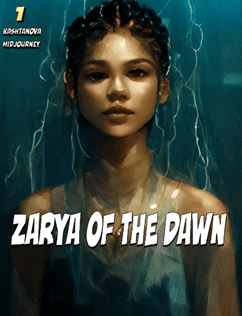

The USA is setting the bar particularly high at the moment; if 80 hours of work and thousands of prompts weren’t enough to convince the USCO that Jason Michael Allen’s contribution was sufficient to be considered the author of Theatre of Space Opera, one wonders what level the USCO expects.

China, on the other hand, seems generous in admitting copyright protection for an image of a young woman, although it is questionable whether it is truly sufficiently “original” in the sense required in principle by copyright.

So it all depends on where you want to place the cursor to recognize sufficient causality between the user and the generated result to see in the former the author of the latter.

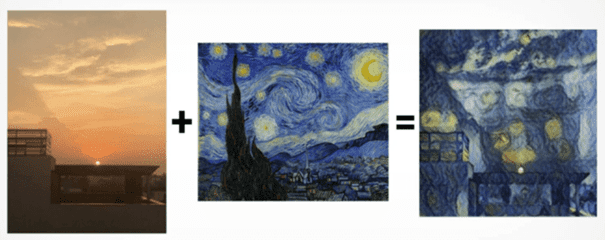

The fundamental question of whether such results deserve protection in view of the raison d’être of copyright, i.e. to encourage creation, should also be asked. Should I be granted such rights to an “artistic” result, despite the fact that I have no real skills to do so, and that my only qualities lie in the ability to do effective prompting?

Could prompting be considered the equivalent of a paintbrush, as Jason Michael Allen argued, an argument the USCO refused to hear? But wouldn’t this be taking the risk of levelling copyright downwards, by conferring such rights on the vast majority of users? What’s more, wouldn’t this be tantamount to levelling down the required level of creativity, by ultimately granting copyright over millions of works generated every day? How high should the bar be set? These are all questions that deserve to be asked, and to which no definitive answers have yet been found (for a discussion of these issues, see Damian Flisak‘s interesting contribution).

Do you have questions about his topic?

Our lawyers benefit from their perfect understanding of Swiss and international business law. They are highly responsive and work hard to find the best legal and practical solution to their clients’ cases. They have acquired years in international experience in business law. They speak several foreign languages and have access to correspondents all over the world.

Avenue de Rumine 13

PO Box

CH – 1001 Lausanne

+41 21 711 71 00

info@wg-avocats.ch

©2024 Wilhelm Attorneys-at-Law Corp. Privacy Policy – Made by Mediago